As I ponder ideas for my next book, it occurred to me that novelists rarely consider the topic of risk. In other areas of life we pay constant heed to it – can I afford to take out a mortgage? Should I look for a new job? We weigh up the pros and cons, the trade-offs between taking a calculated gamble and playing it safe, and decide what’s best for us.

Do novelists ever sit down at the outset of a project and consider this trade-off? Or do we just get seduced by the glimmer of an idea, and spend the next two or three years chasing that ghost?

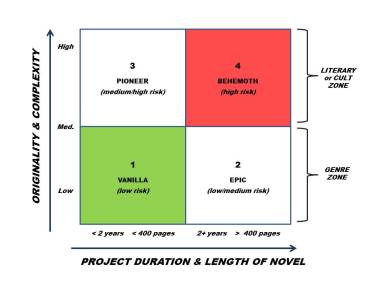

As I wrestled with this question, I decided to adapt a classic risk matrix used in the business world to help me consider my next project. Here’s what my Novelist Risk Matrix looks like:

The vertical axis considers originality and complexity, the horizontal the estimated time taken to write the novel and the physical size of it. Once you assess your idea using these criteria, it lands in one of four boxes…

VANILLA: low on originality and complexity, and short to regular in size. This is the lowest risk category – genre fiction following a fairly standard formula. The easiest to write and read, the writer runs a lower risk of rejection or of not finding an audience. Vanilla does not necessarily mean that the book is lower in quality (although of course many people are snobbish about genre fiction) but it does mean you are competing on a busy playing field.

PIONEER: a short to regular sized book which is original and complex enough to veer away from genre fiction. Pioneer books can sometimes create new genres – think of Harry Potter, which took an old-fashioned genre, re-booted the storyline into something original, and created a sensation. While anyone nowadays writing a book about boy wizards would be firmly in the Vanilla box, when Rowling wrote the first book it was something of a gamble.

EPIC: a hefty genre book – think of the fantasy or sci-fi section in any bookstore where a high percentage of those print books are over 400 pages long. The size of the project makes it riskier than Vanilla books, but it should still be fairly easy to plot a course and follow a formula.

BEHEMOTH: an original and complex book that’s also huge in size. This represents the biggest risk for a writer – undertaking a massive project which may take several years, has no real precursor and potentially has no clear audience at the finish line.

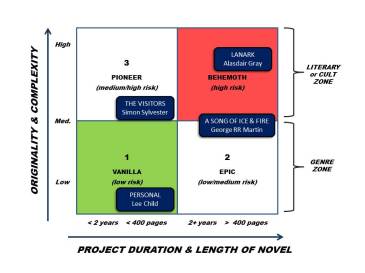

To make it a bit more concrete, here are four novels plotted onto the Novelist Risk Matrix:

I’ve not read ‘Personal’ by Lee Child but a glance at the Amazon best-seller chart made it an obvious candidate for an example of a Vanilla book. The 17th book in his Jack Reacher series, Child is writing to an established formula in an established genre. There is practically no risk for him in writing Jack Reacher books, unless you count the risk that readers may eventually get bored of the character.

Moving north, Simon Sylvester’s ‘The Visitors’ is a good example of a Pioneer. Sylvester took elements of established genres (crime, Young Adult) and fused these familiar components with the ancient Scottish folk tale of the selkies (seal people) into something fresh, surprising and original. Additionally, a strong sense of place and vivid characters make it stand out from the pack. It was probably not an easy book to write, and an agent or editor might wonder how to pitch it, but Sylvester’s gamble paid off – the novel recently won The Guardian’s Not The Booker Prize and is building a growing reputation as a cult book.

Bottom right, Game of Thrones writer George RR Martin took a risk when he sat down to write the first book in the series, which is over 800 pages long. While the swords n’ sorcery themes has an established audience, his highly explicit content did make it riskier than other books in the genre.

Finally, top right, the riskiest of the lot. Alasdair Gray’s ‘Lanark’ is a great example of a Behemoth. A novel consisting of four books following two separate storylines, one set in Glasgow and the other in the surreal dystopian city of Unthank, it took Gray almost 30 years to write. A blend of Scottish realist fiction, fantasy and science-fiction, it is a totally uncategorisable book. Imagine the drive and passion it would take to work on the same novel for nearly thirty years. Luckily for Gray, his genius was recognised, but any novelist setting out on such a project would be well-advised to take a step back for a moment and consider the impact of such a project on their life (and sanity, probably).

So did this process help me? Well, I realised that I simply don’t have the heart for an Epic or a Behemoth. Like most writers, I have a day job, and pint-sized Amsterdam Rampant took me around three years to write. So by that logic my next book will either be Vanilla or a Pioneer. But I know myself too well – I can never really stick to a formula when it comes to writing a novel, so that puts me in the Pioneer box. The trick is for me not to go too far north, but keep within touching distance of Vanilla – a novel that has a recognisable target audience, that follows certain conventions, but is daring enough to surprise and challenge the reader. In ice-cream speak… a small spoonful of vanilla with a fist-sized scoop of chocolate, whisky and chilli.

Pingback: Chasing Ghosts - Todd DeanTodd Dean

Working on a book for thirty years? I’ve only managed fourteen. And that’s bad enough, let me tell you. 🙂